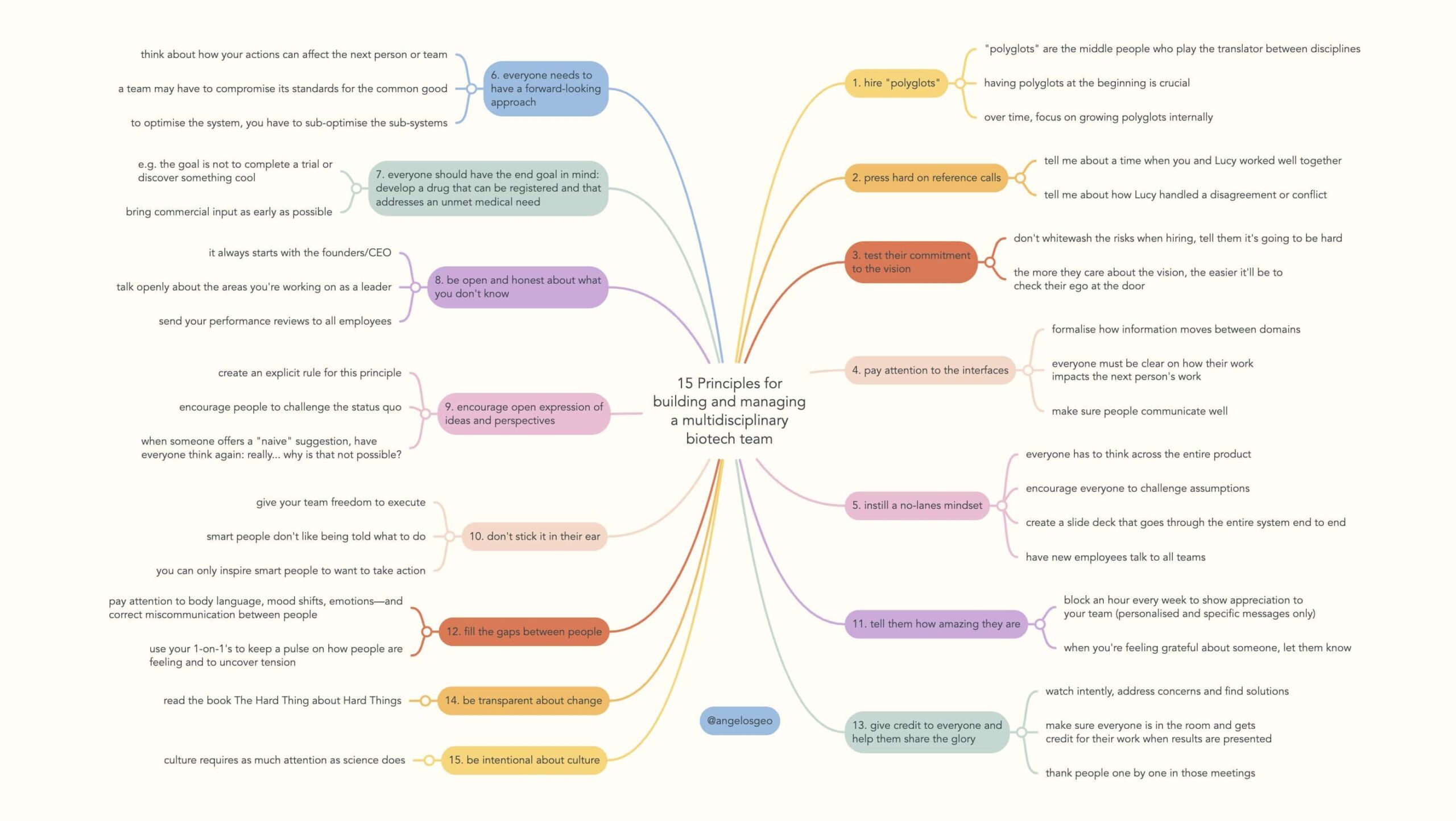

15 principles for building and managing a multidisciplinary biotech team:

1. Hire “polyglots”.

“It’s hard to build a multidisciplinary team from hyper-disciplinarians. People who speak multiple languages have an easier time learning another one.” — George Church

“Bilinguals can bridge the chasm and play the role of the translator between disciplines. They are rare but having those at the very beginning is extremely valuable. Over time, focus on growing bilinguals internally.” — Daphne Koller, CEO at Insitro

Sri Kosuri and the team at Octant Bio call themselves “ante-disciplinary”, i.e. they hire generalists who are working across domains. “It has downsides but it’s the only way to tackle hard problems and chart new approaches in drug discovery.” — Sri Kosuri, CEO at Octant Bio

2. Press hard on those reference calls.

This is something that first-time founders and CEOs like to skip. There’s no way you can hire Lucy unless you’ve interrogated some people that Lucy has worked with in the past.

So, you don’t just ask, “is Lucy a team player?” You want to really dig in:

• Tell me about a time when you and Lucy worked well together

• Tell me about how Lucy handled a disagreement or conflict

• How did Lucy change after receiving feedback from you or the team?

• How did Lucy go above and beyond to support the team?

3. Test their commitment to the vision.

Don’t whitewash the risks when hiring. Tell them they’re singing up for the scariest roller coaster ever. But, if you succeed, you’ll redefine human health. You want the right people to select in.

Hiring people who are bought into the vision is a first-level immunisation against bad culture. Because when people are willing to die for a cause, they are more likely to set aside their ego for the benefit of the team when conflicts arise.

4. Pay attention to the interfaces.

You have all these amazing people who are experts in their fields. The problem—and your biggest challenge—is that these people speak their own language and do things their own way.

You have to build a translation layer and formalise the way that information moves between domains.

Everyone in the team must be clear on:

• where their work is

• how their work impacts the next person’s work

• what are the requirements of the next person and why

From Day #1 the founder/CEO has to facilitate the dialogue between domains to build those cross-cultural bridges and make sure people communicate well with each other.

5. Instill a “no-lanes” mindset.

Although everyone’s responsible for their own area of expertise, there’s no such thing as “you stay in your bio lane, you stay in your data lane”. Everyone has to think across the entire product and understand how all the pieces fit together. Encourage everyone to challenge assumptions.

Hani Goodarzi, Associate Professor at UCSF, says: “I don’t think in wet or dry terms anymore, I just think in terms of problems and solutions. It’s always a problem that we as a team are trying to solve.”

The onboarding process is critical. Create a slide deck that gives a complete picture of the whole system end to end, with all the different disciplines and interfaces. Have new employees talk to all teams.

6. Everyone needs to have a forward-looking approach.

In drug development, there’s nothing that a person or team can do without affecting another person or team. Often, best practices in one team may create problems in another team which means that a team may have to compromise its standards for the common good.

Remember the classic from Systems Theory: “to optimise the system, you have to sub-optimise the sub-systems.”

Say to your people, “You are not a data scientist, you are not a computational biologist, you are not a research associate. Your job is not your job. Your job is to help the team win.” The ultimate purpose of whatever you do is to help someone else in the team, and by induction, to help the whole team win.

7. Everyone should have the end goal in mind.

It’s very easy for a team to get so immersed in what they’re doing and lose the forest for the trees. The goal is not to complete a trial or discover something cool.

Everyone should do their work with the end goal in mind: to develop a drug that can be registered and that addresses an unmet medical need. That’s why it’s crucial to bring in commercial input as early as possible.

The forward-looking approach applies to partners, pharma, and regulators too. There’s always a recipient of your work either inside or outside the company. The key is to be mindful of the recipient’s requirements right from the start and throughout the process.

8. Be open and honest about what you don’t know.

Humility—like all virtues—is modelled at the top. If the leaders are open about their blind spots, the team will be too. If the leaders won’t admit their gaps and weaknesses, the team won’t either.

Talk openly in all-hands meetings: “These are the areas I’m working on and I need your help”. Send your performance reviews from the board to everyone in the team.

9. Encourage open expression of perspectives and ideas.

Make an explicit rule for this principle. Talk about it—and walk the talk. Again, it starts with the CEO and executive team.

When someone asks a “stupid” question or comes up with a “naive” suggestion: “Why don’t we do x?” Instead of saying, “because this is not how it’s done”, have everyone think about it: “really… why don’t we do x?” This can lead not only to better answers but better questions.

10. Don’t stick it in their ear.

You’ve hired these brilliant people, now trust them with the freedom to execute. You don’t tell smart people what to do. Smart people don’t respond well to that. What you do is, hopefully, you inspire them to want to take action.

11. Tell them how amazing they are; Knowing is not enough.

Everyone is an expert in their field and wants to be acknowledged and celebrated. Add a weekly “love the team” block in your calendar to show them your appreciation. One by one, not a “hey everyone” in Slack!

When you catch yourself feeling grateful about someone or something they’ve done, let them know. When you hear something nice said about someone, let them know. And be specific: “Jen, I appreciate you for updating those process documents”.

12. Fill the gaps between people.

Pay attention to body language, mood shifts, and side conversations. Spot when someone is frustrated. Listen and watch intently to correct miscommunication. Use your 1-on-1’s to keep a pulse on how people are feeling and to uncover tension.

13. Give credit to everyone and help them share the glory.

Your goal is to be a good parent to all your children: lab scientists, data scientists, engineers, etc. For example, lab scientists may see the help offered by data scientists as “threatening to their glory”.

Address and discuss these concerns with the teams. For example, a solution could be that the wet lab doesn’t completely hand it off to the data team. They may decide to do the analysis and/or the presentation together. Make sure everyone is in the room and gets credit for their work when results are presented. Again, thank people one by one in those meetings.

14. Be transparent about change.

In a biotech company, things change so rapidly: priorities, targets, strategy… There are so many transition points: from preclinical to clinical, from private to public, from clinical to commercial.

You have to be transparent about these transitions if you want to retain your incredibly talented people and attract new talent when you need them. Everyone has to be clear on where they stand and how their circumstances might change.

The best book I’ve found on this topic is The Hard Thing About Hard Things by Ben Horowitz. There is no playbook for being a CEO, but what this book does is it helps you see the company and your decisions through everyone else’s eyes.

15. Building a great company culture is not rocket science. However…

Founders/CEOs see culture as an elusive thing because simply they’re not intentional about it. Building culture is easier than designing the right molecule for the target. However, if all your attention is on the molecule and you ignore the health of your company, there’s no way you can get the molecule right. Bad culture will break the company. Team building and company culture require as much attention as science does. I call it “the leadership gym”. Your muscles and body need exercise to be strong; the same applies to culture and leadership. It takes attention, it takes time, it takes reps.